Jack Riley was watching the movie “Miracle” with his Mercyhurst teammates when the scene about Herb Brooks getting cut from the 1960 U.S. Olympic team was being discussed by his 1980 players. In the movie, Jim Craig mentioned how Brooks was a late cut by coach Jack Riley, and then the light went on in a couple of minds.

Some Mercyhurst players knew about the relationship to their teammate but there’s always one or two who are new to the story.

“Is that related to you?” asked one player.

“Yeah, that’s my grandfather,” Riley replied.

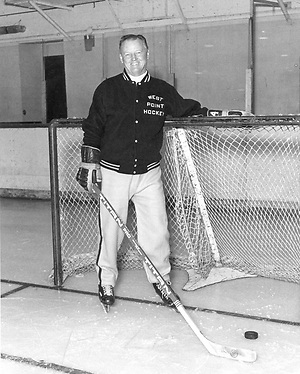

And when Mercyhurst visited West Point recently, there was the elder Jack Riley’s name adorning a banner in Tate Rink. Again, the younger Jack Riley had to explain how his grandfather played in the 1948 Olympics and coached the famed 1960 group that was the first American team to win Olympic gold and coached Army to 542 wins over 36 seasons.

Bloodlines run strong in our lives — politics have the Kennedys, Bushes and Clintons, and college hockey has the Rileys.

The elder Jack Riley, 94, was a standout at Dartmouth before embarking on his coaching career. Sons Rob Riley and Brian Riley were rink rats at West Point’s old Smith Rink, became collegiate players at Boston College and Brown, respectively, and then followed their father behind the Army bench. Rob coached 18 seasons and Brian is in his 11th season.

Son Jay played hockey at Harvard and was an assistant coach at Brown for three seasons. Son Mark played for Boston College. Daughter Mary Beth played hockey for St. Lawrence.

Bill Riley, Jack’s brother, played for Boston University and coached 24 seasons, most of them at UMass-Lowell. Bill’s son, Bill, coaches at The Groton School in Massachusetts. Rob’s son, Brett, just completed four years as a player at Hobart and now coaches the Albany Academy boys’ team in New York.

So it was only natural that Brian’s son, Jack, would follow in the family business. Jack Riley honed his skills at Tate Rink and has become a third-generation Division I player at Mercyhurst.

“I am lucky to be where I am,” Jack said. “I’ve had all the help with my dad, my uncles and grandfather paving the way for me. Everywhere I went was around hockey. It’s just awesome.”

Brian is the first to say his son is a much better player than he ever was, a point Jack is backing up with his steady play for the Lakers.

Jack has twice been named the Atlantic Hockey rookie of the week and he earned top rookie honors for December within the league and by the Hockey Commissioners Association.

He enjoyed a storybook weekend at West Point in December, posting two goals and two assists against his father’s Army team. He’s tied for second in Mercyhurst team scoring with 20 points, and his point-scoring streak reached eight games before ending last Friday against Holy Cross.

“What I noticed about Jack was his IQ … he’s a really smart hockey player,” said Canisius coach Dave Smith. “His skills are great and he is somebody who in the future and right now we have to pay attention to.”

Even though he was exposed to hockey year round, Jack said he was never forced to play the sport.

“I love the game, ever since watching my dad’s teams,” said Jack, who also played high school soccer and lacrosse. “I know that is what I wanted to do — I wanted to become a Division I hockey player.”

What Jack said he appreciates the most is that his father was not a crazy hockey dad, and when hockey was over it was back to being father and son.

“He walked me through a game,” Jack said. “If he noticed a mistake he would let me know in a nice manner and coached me the right way. I loved having him around, teaching me.”

It’s the same manner in which Brian, Rob, Jay and Mary Beth were introduced to the sport by their famous dad.

“My dad was a great player in college and player-coach in the Olympics and coached in the Olympics but never once did he make me feel or my brothers and sister that we had to play hockey or we had to be as good as him,” Brian said. “I consider myself very lucky to have had the opportunity to be around my dad and kind of learn about his hockey experiences. It’s obviously what drove me to the sport but I never felt pressure that I had to play.

“I can’t remember one time where I ever sat in the car with him or at the house and said, ‘Oh god, this guy is all over me here,’ or putting pressure on me to be the type of player that he was,” Brian said of his dad. “From that standpoint I was really lucky, and I tried with my own kids not to be that type of parent that would make my kids feel like they had to play hockey or live up to any expectations. I wanted them to play hard and have fun.”

Brian may have learned more about how to be a coach than a player while sitting at the family kitchen table at West Point, often visited by players and assistant coaches.

“He had people over there, drawing up power plays and just learning about the game,” Brian said. “Another huge benefit was having the opportunity to get on the ice. I would get off the [school] bus when I was in high school and get off at the rink and jump on with his team. It was a huge, huge benefit for me. It was something I wanted to do, to be around the rink and be around his team.”

Likewise, Jack has learned a lot about the game by watching Rob and Brian run their Army teams behind the bench. Rob went on to coach Springfield in the AHL for two seasons, and now is the athletic director at Regis College near Boston.

“I definitely benefited from it, just seeing the way they coach their teams,” Jack said. “I learned a lot sitting above them, listening to the things that he said and the way he talked to his guys and the drills they run in practice. I was able to pick up that at a young age that a lot of players my age weren’t able to do. It was good to have those role models.”

“Jack, even at an early age, I would bring him to games and he would just watch,” Brian said. “Usually with little kids it’s hard for them to sit still but he watched the games. One of Jack’s strengths is his hockey sense, and part of that was developed because he was always a student of the game.”

When the elder Jack Riley was inducted into the Olympic Hall of Fame in Lausanne, Switzerland, it was the first time Brian had seen film footage of his father playing hockey. “I was just blown away by what I saw and how good of a player he really was,” Brian said.

That experience filled a tiny void for Brian, but he values the family experience more than hockey.

“I tell people all the time that everybody knows him as Coach Riley,” Brian said. “But the most important thing is I get to call him dad. As great a coach as he was, as great a player that he was, he was an even better father. When it was all said and done, I hope my kids will be able to say the same thing.”

Jack played only seven games in his freshman season a year ago before being forced into having hip surgery. He has returned fully healthy in his redshirt year and is looking to add to the Riley legacy.

“Now I am hitting my stride and living my dream,” Jack said.